What, When, Where, How, Who?

Time

Introduction, Basic Definitions and Related Concepts:

Time is a basic component of the measuring system used to sequence events, to compare the durations of events and the intervals between them, and to quantify the motions of objects. Time has been a major subject of religion, philosophy, and science, but defining time in a non-controversial manner applicable to all fields of study has consistently eluded the greatest scholars. In physics and other sciences, time is considered one of the few fundamental quantities.[2] Time is used to define other quantites – such as velocity – and defining time in terms of such quantities would result in circularity of definition.[3] An operational definition of time, wherein one says that observing a certain number of repetitions of one or another standard cyclical event (such as the passage of a free-swinging pendulum) constitutes one standard unit such as the second, has a high utility value in the conduct of both advanced experiments and everyday affairs of life. The operational definition leaves aside the question whether there is something called time, apart from the counting activity just mentioned, that flows and that can be measured. Investigations of a single continuum called space-time brings the nature of time into association with related questions into the nature of space, questions that have their roots in the works of early students of natural philosophy. Among philosophers, there are two distinct viewpoints on time. One view is that time is part of the fundamental structure of the universe, a dimension in which events occur in sequence. Sir Isaac Newton subscribed to this realist view, and hence it is sometimes referred to as Newtonian time.[4][5] The opposing view is that time does not refer to any kind of "container" that events and objects "move through", nor to any entity that "flows", but that it is instead part of a fundamental intellectual structure (together with space and number) within which humans sequence and compare events. This second view, in the tradition of Gottfried Leibniz[6] and Immanuel Kant,[7][8] holds that time is not itself some thing and therefore is not to be measured. Temporal measurement has occupied scientists and technologists, and was a prime motivation in astronomy. A religion is a set of beliefs and practices often organized around supernatural and moral claims, and often codified as prayer, ritual, and religious law. Religion also encompasses ancestral or cultural traditions, writings, history, and mythology, as well as personal faith and mystic experience. The term "religion" refers to both the personal practices related to communal faith and to group rituals and communication stemming from shared conviction. In the frame of European religious thought,[1] religions present a common quality, the "hallmark of patriarchal religious thought": the division of the world in two comprehensive domains, one sacred, the other profane.[2] Religion is often described as a communal system for the coherence of belief focusing on a system of thought, unseen being, person, or object, that is considered to be supernatural, sacred, divine, or of the highest truth. Moral codes, practices, values, institutions, tradition, rituals, and scriptures are often traditionally associated with the core belief, and these may have some overlap with concepts in secular philosophy. Religion is also often described as a "way of life". The development of religion has taken many forms in various cultures. "Organized religion" generally refers to an organization of people supporting the exercise of some religion with a prescribed set of beliefs, often taking the form of a legal entity (see religion-supporting organization). Other religions believe in personal revelation. "Religion" is sometimes used interchangeably with "faith" or "belief system,"[3] but is more socially defined than that of personal convictions. The English word religion is in use since the 13th century, loaned from Anglo-French religiun (11th century), ultimately from the Latin religio, "reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety, the res divinae".[4] Philosophy is the discipline concerned with questions of how one should live (ethics); what sorts of things exist and what are their essential natures (metaphysics); what counts as genuine knowledge (epistemology); and what are the correct principles of reasoning (logic).[1][2] The word is of Ancient Greek origin: φιλοσοφία (philosophía), meaning love of wisdom.[3] Every definition of philosophy is controversial. The field has historically expanded and changed depending upon what kinds of questions were interesting or relevant in a given era. It is generally agreed that philosophy is a method, rather than a set of claims, propositions, or theories. Its investigations are based upon rational thinking, striving to make no unexamined assumptions and no leaps based on faith or pure analogy. Different philosophers have had varied ideas about the nature of reason. There is also disagreement about the subject matter of philosophy. Some think that philosophy examines the process of inquiry itself. Others, that there are essentially philosophical propositions which it is the task of philosophy to answer.[4] Although the word "philosophy" originates in Ancient Greece, many figures in the history of other cultures have addressed similar topics in similar ways.[5] The philosophers of East and South Asia are discussed in Eastern philosophy, while the philosophers of North Africa and the Middle East, because of their strong interactions with Europe, are usually considered part of Western philosophy. In its broadest sense, science (from the Latin scientia, meaning "knowledge") refers to any systematic knowledge or practice. In its more usual restricted sense, science refers to a system of acquiring knowledge based on the scientific method, as well as to the organized body of knowledge gained through such research.[1][2] Fields of science are commonly classified along two major lines:

- Natural sciences, which study natural phenomena (including biological life), and Social sciences, which study human behavior and societies.

These groupings are

empirical sciences, which means the knowledge must

be based on

observable

phenomena and capable of being

experimented for its

validity by other researchers working under the same

conditions.[2]

Mathematics, which is sometimes classified within a

third group of science called

formal science, has both similarities and

differences with the natural and social sciences.[2]

It is similar to

empirical sciences in that it involves an objective,

careful and systematic study of an area of knowledge; it

is different because of its method of verifying its

knowledge, using

a priori rather than empirical methods.[2]

Formal science, which also includes

statistics and

logic, is vital to the empirical sciences. Major

advances in formal science have often led to major

advances in the physical and biological sciences. The

formal sciences are essential in the formation of

hypotheses,

theories, and

laws,[2]

both in discovering and describing how things work

(natural sciences) and how people think and act (social

sciences). Sometimes termed

experimental science to differentiate it from

applied science, which is the application of

scientific research to specific human needs, though the

two are often interconnected. The word science

comes through the

Old French, and is derived from the

Latin word scientia

for

knowledge, the nominal form of the verb

scire, "to

know". The

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root that yields scire

is *skei-, meaning to "cut, separate, or

discern". Physics is the

science of

matter[1]

and its

motion,[2][3]

as well as

space and

time[4][5]

— the

science that deals with concepts such as

force,

energy,

mass, and

charge. Physics is an

experimental

science;[6]

it is the general analysis of

nature, conducted to understand how the world around

us behaves.[7]

Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines,

having

emerged as a modern science in the 17th century,[8]

and through its modern subfield of

astronomy, it may be the oldest of all.[9]

Those who work professionally in the field are known as

physicists. Advances in physics often translate to

the technological sector, and sometimes influence the

other sciences, as well as mathematics and philosophy.

For example, advances in the understanding of

electromagnetism have led to the widespread use of

electrically driven devices (televisions, computers,

home appliances etc.); advances in

thermodynamics led to the development of motorized

transport; and advances in

mechanics led to the development of

calculus,

quantum chemistry, and the use of instruments such

as the

electron microscope in

microbiology. Today, physics is a broad and highly

developed subject. Research is often divided into four

subfields: condensed matter physics; atomic, molecular,

and optical physics; high-energy physics; and astronomy

and astrophysics. Most physicists also specialize in

either

theoretical or

experimental research, the former dealing with the

development of new theories, and the latter dealing with

the experimental testing of theories and the discovery

of new phenomena. Despite important discoveries during

the last four centuries, there are a number of

unsolved problems in physics, and many areas of

active research. Fundamental means

serving as an original or generating source : primary

<a discovery fundamental to

modern computers>

serving as a basis

supporting existence or determining essential structure

or function : basic

of or relating to

essential structure, function, or facts : radical

<fundamental change>;

also

: of or dealing with general principles

rather than practical application <fundamental

science>

adhering to

fundamentalism

of, relating to, or produced by the lowest component of

a complex vibration

of central importance : principal

<fundamental purpose>

belonging to one's

innate or ingrained characteristics : deep-rooted

<her fundamental good humor>.

Quantity is a kind of

property which exists as magnitude or multitude. It is

among the basic classes of things along with

quality,

substance,

change, and

relation. Quantity was first introduced as

quantum, an

entity having quantity. Being a fundamental term,

quantity is used to refer to any type of quantitative

properties or attributes of things. Some quantities are

such by their inner nature (as number), while others are

functioning as states (properties, dimensions,

attributes) of things such as heavy and light, long and

short, broad and narrow, small and great, or much and

little. One form of much, muchly is used to say that

something is likely to happen. A small quantity is

sometimes referred to as a quantulum. Two basic

divisions of quantity,

magnitude and multitude (or

number), imply the principal distinction between

continuity (continuum)

and

discontinuity. Under the names of multitude come

what is discontinuous and discrete and divisible into

indivisibles, all cases of collective nouns: army,

fleet, flock, government, company, party, people,

chorus, crowd, mess, and number. Under the names of

magnitude come what is continuous and unified and

divisible into divisibles, all cases of non-collective

nouns: the universe, matter, mass, energy, liquid,

material, animal, plant, tree. Along with analyzing

its nature and classification, the issues of quantity

involve such closely related topics as the relation of

magnitudes and multitudes, dimensionality, equality,

proportion, the measurements of quantities, the units of

measurements, number and numbering systems, the types of

numbers and their relations to each other as numerical

ratios. Thus quantity is a property that exists in a

range of magnitudes or multitudes. In

physics, velocity is defined as the

rate of change of

position. It is a

vector

physical quantity; both speed and direction

are required to define it. In the

SI (metric) system, it is measured in

metres per second: (m/s) or ms-1. The

scalar

absolute value (magnitude)

of velocity is

speed. For example, "5 metres per second" is a

scalar and not a vector, whereas "5 metres per

second east" is a vector. The average velocity

v of an object moving through a displacement

during a time interval (Δt)

is described by the formula:

during a time interval (Δt)

is described by the formula:

The rate of change of velocity is referred to as

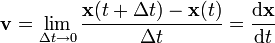

acceleration. The instant velocity vector v

of an object that has positions x(t) at

time t and x(t+Δt)

at time t+Δt, can be

computed as the

derivative of position:

The rate of change of velocity is referred to as

acceleration. The instant velocity vector v

of an object that has positions x(t) at

time t and x(t+Δt)

at time t+Δt, can be

computed as the

derivative of position:

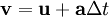

The equation for an object's velocity can be obtained

mathematically by taking the

integral of the equation for its acceleration

beginning from some initial period time

t0 to some

point in time later tn.

The final velocity v of an object which starts

with velocity u and then accelerates at constant

acceleration a for a period of time

(Δt) is:

The equation for an object's velocity can be obtained

mathematically by taking the

integral of the equation for its acceleration

beginning from some initial period time

t0 to some

point in time later tn.

The final velocity v of an object which starts

with velocity u and then accelerates at constant

acceleration a for a period of time

(Δt) is:

The average velocity of an object undergoing constant

acceleration is

The average velocity of an object undergoing constant

acceleration is

,

where u is the initial velocity and v is

the final velocity. In

logic, begging the question has traditionally

described a type of

logical fallacy (also called petitio principii)

in which the proposition to be proved is assumed

implicitly or explicitly in one of the premises.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Begging the question is related to the fallacy

known as circular argument, circulus in

probando, vicious circle or circular

reasoning. The first known definition in the West is

by the

Greek

philosopher

Aristotle around

350 B.C., in his book

Prior Analytics. In recent decades, "begs the

question" has been used increasingly but incorrectly to

mean that a statement invites another obvious question.[7]

The Latin term was incorporated into

English in the

16th century. The Latin version, Petitio

Principii (from peto, petere, petivi, petitus:

attack, aim at, desire, beg, entreat, ask (for), reach

towards, make for; principii, genitive of

principium: beginning or principle), literally means

"begging or taking for granted of the beginning or of a

principle." That is, the premise (the principle, the

beginning) depends on the truth of the very matter in

question. The Latin phrase comes from the

Greek en archei aiteisthai in

Aristotle's Prior Analytics II xvi:

,

where u is the initial velocity and v is

the final velocity. In

logic, begging the question has traditionally

described a type of

logical fallacy (also called petitio principii)

in which the proposition to be proved is assumed

implicitly or explicitly in one of the premises.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Begging the question is related to the fallacy

known as circular argument, circulus in

probando, vicious circle or circular

reasoning. The first known definition in the West is

by the

Greek

philosopher

Aristotle around

350 B.C., in his book

Prior Analytics. In recent decades, "begs the

question" has been used increasingly but incorrectly to

mean that a statement invites another obvious question.[7]

The Latin term was incorporated into

English in the

16th century. The Latin version, Petitio

Principii (from peto, petere, petivi, petitus:

attack, aim at, desire, beg, entreat, ask (for), reach

towards, make for; principii, genitive of

principium: beginning or principle), literally means

"begging or taking for granted of the beginning or of a

principle." That is, the premise (the principle, the

beginning) depends on the truth of the very matter in

question. The Latin phrase comes from the

Greek en archei aiteisthai in

Aristotle's Prior Analytics II xvi:

Begging or assuming the point at issue consists (to take the expression in its widest sense) in failing to demonstrate the required proposition. But there are several other ways in which this may happen; for example, if the argument has not taken syllogistic form at all […]. If, however, the relation of B to C is such that they are identical, or that they are clearly convertible, or that one applies to the other, then he is begging the point at issue.

Fowler's Deductive Logic (1887) argues that the Latin origin is more properly Petitio Quæsiti which translates as "begging the question". A definition is a statement of the meaning of a word or phrase. The term to be defined is known as the definiendum (Latin: that which is to be defined). The words which define it are known as the definiens (Latin: that which is doing the defining).[1] A definition may either give the meaning that a term bears in general use (a descriptive definition), or that which the speaker intends to impose upon it for the purpose of his or her discourse (a stipulative definition). Stipulative definitions differ from descriptive definitions in that they prescribe a new meaning either to a term already in use or to a new term. A descriptive definition can be shown to be right or wrong by comparison to usage, while a stipulative definition cannot. A stipulative definition, however, may be more or less useful. A kind of often useful stipulative definitions are precising definitions. A persuasive definition, named by C.L. Stevenson, is a form of stipulative definition which purports to describe the 'true' or 'commonly accepted' meaning of a term, while in reality stipulating an altered use, perhaps as an argument for some view, for example that some system of government is democratic. Stevenson also notes that some definitions are 'legal' or 'coercive', whose object is to create or alter rights, duties or crimes.[2] An intensional definition, also called a connotative definition, specifies the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing being a member of a specific set. Any definition that attempts to set out the essence of something, such as that by genus and differentia, is an intensional definition. An operational definition is a showing of something — such as a variable, term, or object — in terms of the specific process or set of validation tests used to determine its presence and quantity. Properties described in this manner must be publicly accessible so that persons other than the definer can independently measure or test for them at will. An operational definition is generally designed to model a conceptual definition. The most basic operational definition is a process for identification of an object by distinguishing it from its background of empirical experience. The binary version produces either the result that the object exists, or that it doesn't, in the experiential field to which it is applied. The classifier version results in discrimination between what is part of the object and what is not part of it. This is also discussed in terms of semantics, pattern recognition, and operational techniques, such as regression. For example, the weight of an object may be operationally defined in terms of the specific steps of putting an object on a weighing scale. The weight is whatever results from following the measurement procedure, which can in principle be repeated by anyone. It is intentionally not defined in terms of some intrinsic or private essence. The operational definition of weight is just the result of what happens when the defined procedure is followed. In other words, what's being defined is how to measure weight for any arbitrary object, and only incidentally the weight of a given object. The second (SI symbol: s), sometimes abbreviated sec., is the name of a unit of time, and is the International System of Units (SI) base unit of time. SI prefixes are frequently combined with the word second to denote subdivisions of the second, e.g., the millisecond (one thousandth of a second) and nanosecond (one billionth of a second). Though SI prefixes may also be used to form multiples of the second (such as “kilosecond,” or one thousand seconds), such units are rarely used in practice. More commonly encountered, non-SI units of time such as the minute, hour, and day increase by multiples of 60 and 24 (rather than by powers of ten as in the SI system).